1.3.2 Matrix Structures That Work!

A recent article on Cross-Functional Workgroups raised considerable interest and one result was that I have spent time speaking with a freelance journalist who has been commissioned by a magazine to write further on this particular topic.

In order to explain the fundamental characteristics of a Cross-Functional Workgroup (CFW), I use the analogy of a cricket team. If you had twenty-two players to form into two cricket elevens and the players by chance were equally divided between batsmen and bowlers, the composition of each team could take one of two basic forms. You could either select one team made up entirely of bowlers and the other made up of batsmen or you could select a mix of both bowlers and batsmen in each of the two teams.

The former represents a functional structure (everybody in the team performs the same function of either batting or bowling) whereas the latter represents a CFW where in this case, two functions are present in the same team. In the functional structure, the bowlers would attempt to get the batsmen out for the least possible runs to compensate for their woeful batting and the batsmen would want to maximise their score to make up for their poor bowling. However, experience suggests that a team with a mix of batsmen and bowlers is a far more effective use of available resources.

The argument for CFW’s is thus a compelling one and it prompted the journalist to ask: “Why don’t all organisations adopt CFW’s?”

Why indeed? To answer that question, one really needs to trace the evolution of management structures as an organisation grows and becomes more complex. But before doing this, it’s important to understand the purpose of an organisational structure. Thus an organisational structure provides the framework for:

- Identifying and meeting customer needs – now and in the future

- Doing the above as effectively and efficiently as possible

- Competing effectively with one’s competitors

- Providing employees with a satisfying and rewarding place of work

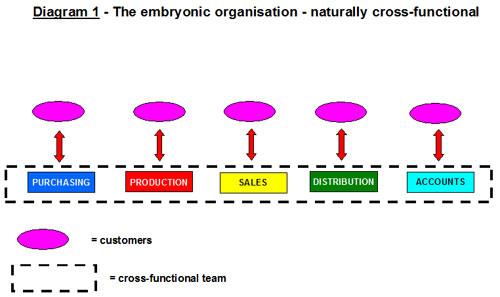

Diagram 1 represents a small manufacturer. There is five staff each looking after a particular function. Each is self-sufficient in his or her particular role. All have a clear picture of the goals of the company and their part in achieving them. They communicate formally and informally with one another and they have a team agenda that takes precedence over personal agendas. They adapt rapidly to changes in the business environment and their decision-making is crisp. They operate naturally as a CFW.

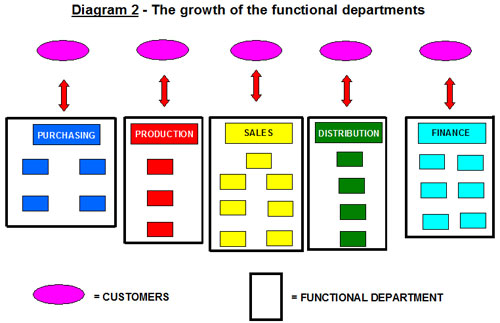

However, as the business grows, it is necessary to take on extra staff. The Production Manager needs a Production Supervisor, the Sales Manager needs Sales Representatives and the Accounts Manager effectively becomes the Finance Manager and can no longer act as book keeper, credit manager and look after accounts receivable. The end result is that the organisational structure develops into the more complex structure depicted in Diagram 2.

Now our managers have a number of reports. They still take responsibility for most decisions but their focus imperceptibly starts to shift from the “big picture” and company goals to departmental ones. Unlike the past, if a manager of another department has a problem, there is some reluctance to lend a hand in resolving it. An attitude of “that’s their problem, not mine” starts to take root. Decision-making is both slower and decisions lean towards what is best for my department rather than what is best for the company as a whole. The managers acquire greater status – they all have a nice company car, the model of which they can choose for themselves and the perks of office start to accumulate.

A number of years ago, I did a customer feedback survey for a company with a national sales network. Each state had its own regional office. Of these offices, the one in South Australia was the smallest and mirrored the organisation depicted in Diagram 1. It was after all, the youngest child of the parent company. The volume of business was insufficient to warrant a team of sales reps so their customers dealt directly with the state managers of the various functions. It came as no surprise to find that customer satisfaction levels among South Australian customers were the highest recorded for any state – by a substantial margin. In contrast the volume of business in other states meant that their organisational structures were starting to look more like the one depicted in Diagram 2. The CFW in Diagram 1 was gradually changing into a functional structure.

Now the point is that management did not sit down one day and decide that the structure was in need of change. No one announced that the company would be better served by reorganising along functional lines. The switch from a cross-functional workgroup to functional departments just happens slowly and imperceptibly. Equally slowly and imperceptibly, the focus on customers needs and the competition declines, led by those departments that have least contact with the external customer.

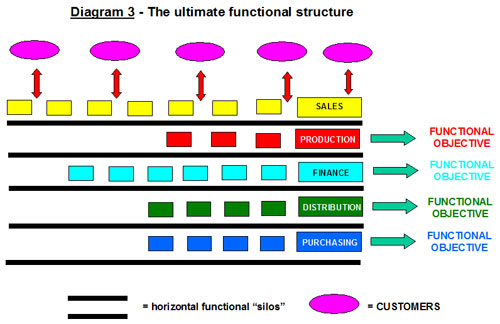

Ultimately, one ends up with a structure illustrated in Diagram 3.

Conventional management jargon often uses the word “silos” to describe the organisational behaviour of the functional departments illustrated above. Silos are stand-alone structures clad in concrete walls that are isolated and independent of one another. Product enters the silo at the top through a specific and carefully monitored entry point and exits the silo at the bottom. But silos are vertical structures and unlike the diagrams here, the customer is not included. I like to view the ultimate functional structure as horizontal strata.

Using this metaphor, the only department with a customer orientation is the Sales department. Geologically speaking, it is the youngest of the strata and the only one that has regular contact with the external customer. Successive strata become ever more remote from the forces of the market place and in their isolation, their focus turns to maximising the performance of their own departments rather than seeking to play their part in maximising the performance of the company as a whole.

I have personal experience of the debilitating impact of organisational structures based on functional departments. Each departmental head had his or her own departmental agenda. Each did their best to impress the GM. The purchasing manager would proudly point to out how they were now sourcing a raw material from Russia at a saving of 20%. The fact that it was of inferior quality was production’s problem, not his. The fact that the end product was inferior was Sales’ problem, not his.

Sales saw the need to add a line addition to the product range but production resisted this because it would impact on the department’s productivity targets.

Distribution changed transport companies because another company offered a better rate. The present transport company was more expensive but highly reliable. It might not have the quickest elapsed time from Victoria to Queensland but Sales had long established that delivery-on-time was more important to its customers than the order turnaround time, especially if the latter was subject to variation.

An over zealous accounts receivable clerk was a legend in her own department for the alacrity with which she put accounts on hold. Too bad that a loyal customer of twenty years standing defected, having understandably refused to pay his account until he had received a credit that was rightly his.

In my company, the functional heads were members of a management committee that met monthly. If there were minutes, they were not passed on to the troops and in their absence, one suspected that whilst lip service might have been paid to the overall optimisation of the business, most effort was expended on short-sighted proposals, turf wars and white-anting each other.

Under this scenario departments develop into fiefdoms, departmental heads acquire more and more power and influence as their departments grow, the whole organisation becomes inward looking and increasingly remote from the market place and the winds of change and competition. Sooner or later, profitability and market share declines to the point where action must be taken. So it’s back to the future with Cross-Functional Workgroups.

I’ll recap the progression to date. At the start our manufacturing company develops naturally into a Cross-Functional Workgroup. Further growth sees the evolution of the one CFW into – in our example – five functional departments. The functional departments continue to expand until the last vestiges of the original CFW are lost in interdepartmental rivalries. Apart from the sales department, other departments lose touch with the realities of the market place.

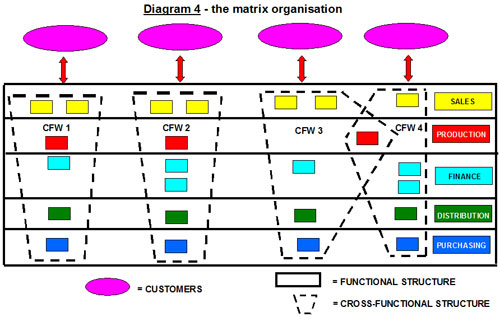

Diagram 4 is essentially the same as Diagram 3 but four CFW’s have been established to service four customer segments. These are represented by the dotted lines. So what we now have is an organisational matrix. Matrix structures are more complex than functional ones but the reality is that large organisations are complex. Indeed this diagram represents a relatively simple two-dimensional matrix. Four-dimensional matrices are not uncommon, covering regional, functional, product based and market based requirements.

However, I can say with a great deal of confidence that the matrix structure in Diagram 4 will not work effectively. The only restructuring that has taken place is the formation of the four CFW’s that are superimposed on an otherwise unchanged organisation. The real power and influence continues to reside with the functional heads. If the new CFW’s are to achieve their design objectives – a refocus of the organisation’s resources on identifying and meeting the needs of customers – ultimate power and influence must be transferred from the departmental heads to the heads of the new CFW’s. And if the CEO is surprised by the alacrity with which the departmental heads agreed to the formation of the CFW’s, this is the reason. This is a Clayton’s matrix – the new CFW’s are toothless tigers.

I can put the issue no clearer than to quote from Lou Gerstner’s book on the restructuring of IBM in the mid 1990’s. This is what he had to say under the heading “Shift the Power”

“One of the most surprising (and depressing) things that I have learned about large organisations is the extent to which individual parts of an enterprise behave in an unsupportive and competitive way towards other parts of the organisation…… Individuals and departments (agencies, faculties, whatever they are called) jealously protect their prerogatives, their autonomy, and their turf.”

“Consequently, if a leader wants fundamentally to shift the focus of an institution, he or she must take power away from the existing “barons” and bestow it publicly on the new barons. Admonishments of “play together children” sometimes work on the playground, they never work in a large enterprise.”

At IBM, to be a truly integrated company, we needed to organise our resources around customers, not products or geographies. However, the geographic and product chieftains “owned” all of the resources. Nothing would have changed (except polite platitudes and timely head nodding) if we didn’t redirect the levers of power. This meant making changes in who controlled the budgets, who signed off on employee’s salary increases and bonuses, and who made the final decisions on prices and investments. We virtually ripped this power from the hands of some and gave it to others.”

“If a CEO thinks he or she is redirecting or reintegrating an enterprise but doesn’t distribute the basic levers of power (in effect, redefining who “calls the shots”), the CEO is trying to push string up a hill.”

Having worked in an organisation that adopted a matrix structure without redistributing the levers of power, I can wholly identify with Lou Gerstner’s comments.

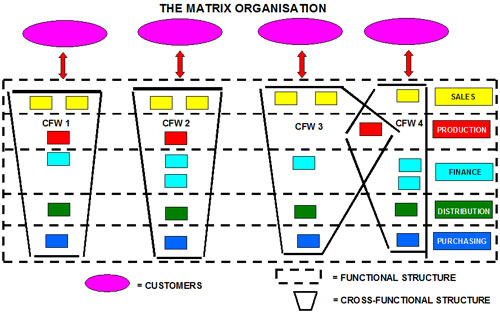

The final diagram does what Gerstner considers to be absolutely essential – it shifts the levers of power to the new CFW’s.

No longer do the functional heads call the shots. Their role is to provide the necessary support to the CFW’s. They might even become surplus to requirements. It is highly unlikely that, with the exception of the sales manager, any of the functional heads would be suitable to manage one of the CFW’s.

When organisational structures are considered in this light, it is not hard to appreciate the obstacles that are put in the way of restructuring along the lines depicted. It becomes apparent that the very people who should be the architects of change are also the people who have most to lose by it.