1.2.12 Gaining Competitive Advantage Through Collaboration And Partnering

Authors note - This article covers a highly topical subject; it examines the reasons why many alliances between members of a supply chain fail to fulfil their potential whilst others go from strength to strength. It summarises the key points contained the recently published book by Kogan Page: “Strategic Alliances & Marketing Partnerships - gaining competitive advantage by collaboration and partnering” written by Dr Andrew Humphries and Dr Richard Gibbs. Both men are highly qualified to address this issue. The research for their PhD’s underpins much of their findings explained in this article.

In recent years, globalisation and the increased sophistication of products and markets have rendered the old style of adversarial relationships between customers and suppliers as redundant. Increasingly, effective partnering is seen as a key capability of the organisation and the most effective strategy for long-term, competitive success.

Nevertheless, the success or failure of such alliances covers a broad spectrum. At one end, many alliances fail to live up to expectations. Often small issues are left unresolved and the relationship enters a downward spiral from which there is no recovery. At the other end, the value that the parties to the alliance foresee drives both sides to invest, to innovate, to achieve customer focus and to communicate freely in a virtuous spiral of collaboration.

Most partnerships exist somewhere between these two extremes and it was the need to determine their position on the spectrum that led Humphries and Gibbs to combine their research to identify the important drivers of relationship performance and to develop the diagnostic tools for their management.

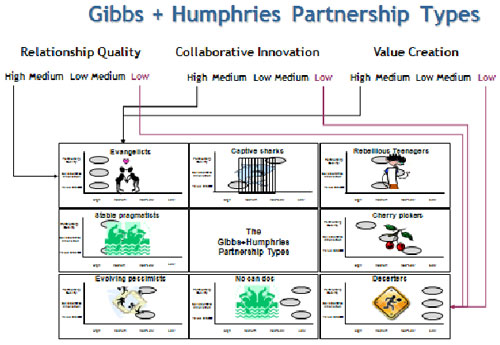

Three “super factors” – collaborative innovation, partnership quality and value creation emerged from the analysis and when plotted against value judgments of alliance success, eight discrete relationship “personalities” were defined. These are the G & H Partnering Types They represent the company partnership equivalent to the Myers Briggs personality profiling. Knowing your specific partnering type enables you and your partner to take tactical and strategic decisions to maximise the value that both parties derive from the relationship.

Through collaboration, business can improve operational processes and reduce costs and time to market. Strategic alliances can be used to bring new skill sets and capabilities into the organisation and enable objectives to be accomplished that would not be possible if acting alone. Most importantly, partnerships can be a long-term source of competitive advantage resulting in higher returns on investment, better gross margins and above average levels of growth. Despite the proven benefits of partnering, many alliances fail to live up to expectations and some 40% are dissolved in their first year.

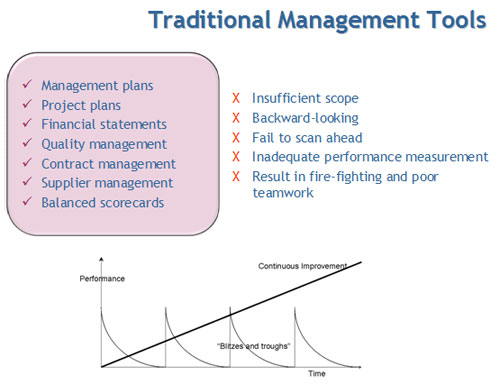

Part of the reason has been the lack of management tools that can measure the state of the relationship rather than historical and specific process outcomes. The latter are lagging indicators of what has happened or what has not happened. They reflect the business needs of one side of the partnership only and interpret the results in the context of the single firm. If the objective measures of performance – quality, delivery, cost etc – are below target, the supplier is held to account and conflict ensues that further damages the relationship. The downward spiral begins.

What has been needed are better management tools, better ways of understanding and discovering the root causes of the partnership challenge and a way of highlighting those actions that will allow the partners to achieve their aims and objectives as efficiently as possible.

Realistically the opportunities for failure points to occur in supply chain relationships are legion. Traditionally management knowledge and learning is all about managing inside one’s own organisation. Looking outside of one’s own organisation and working with other businesses is not generally something that many of us are trained to do. It runs contrary to the natural competitive instinct of any organisation to work close to home and to be wary of company outsiders, be they suppliers, customers or partners.

Beyond these cultural issues, alliance management is an often misunderstood concept. In many organisations the function is dispersed among commercial, sales, operational and senior staff. These people focus on outcomes rather than the relationship that influences them. There is no one single point of contact at each of the partners responsible for coordination, problem resolution, performance management, and planning functions of the joint enterprise.

The problem is compounded by many business schools that continue to teach Supplier Relationship Management and Key Account Management that promotes a self-centred approach rather than Alliance Management that focuses on collaboration. In seeking to foster collaboration, companies must adopt measures that recognise the strategic value of their partnership. Otherwise, they will invite failure.

An example of the wrong sort of relationship and measurements could be the failure of the major supplier of specialist fasteners to the Australian automotive industry. The customers were caught by surprise because their supplier measurement system (focused on cost savings and quality failures) failed to alert them to the impending problem. Propping up the supplier cost them significantly more than having a better understanding of the relationship and the problems that they (the customers) were causing.

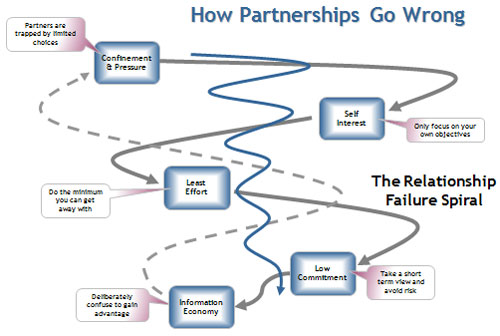

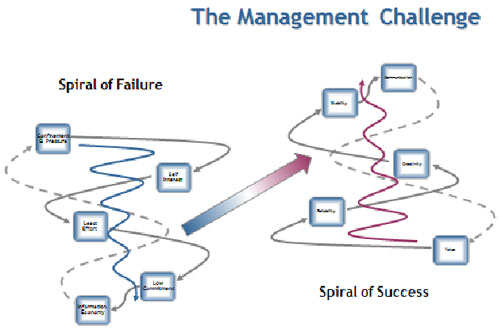

The steps in a failing relationship can be represented by a dynamic relationship spiral with value being the main casualty that suffers as a consequence.

Problems may begin with the partners feeling trapped and under pressure. Trapped in the sense that they feel their independence of action is threatened by their commitment to work with the other party. The feeling of entrapment grows and leads each party to take a very self-interested view of the arrangement. This in turn forms the background to adversarial negotiations where “I win, you lose” replaces the notion of “you win, I win”.

Both parties look to the “fine print”; investment in the partnership of time, energy and resources is kept to a minimum. Both companies start to take a short-term view, sacrificing the long-term profitability and benefits of the partnership for short-term gains. The final step in the spiral downwards is the withholding or manipulation of information to gain advantage. As each party becomes increasingly aware of this, their feeling of entrapment grows still further and the spiral begins again.

But partnerships do not have to end like this. There are many examples where suppliers and customers have supported each other through difficult times based on relationships and understanding. Again from the automotive industry, stories abound about Toyota turning up to help a supplier overcome a problem that that cannot solve alone. The approach being that, once you are in the Toyota supplier family then you will be supported.

This is a policy that is true for any country in which they operate including Australia. It is possible to postulate the reverse of the spiral of failure where a positive feedback loop causes partnership value to rise continuously.

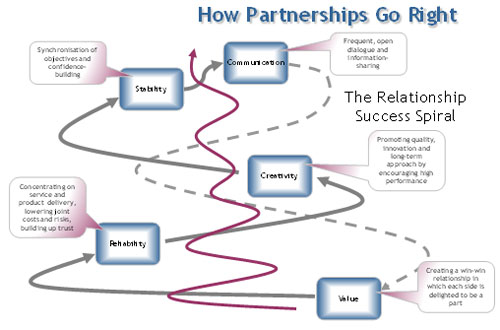

It is possible to postulate the reverse of the spiral of failure where a positive feedback loop causes partnership value to rise continuously.

The starting point for these successful partnerships is an openness and willingness to create value for the partnerships and to recognise that a “win-win” relationship will enable the individual businesses to achieve their goals and ambitions. The creation of value is built upon an overt attention to operational processes and outcomes but especially to the end customer.

Focusing on the needs of the end customer generates an in-depth understanding of how partners can become more effective, more efficient and offer higher quality through the combination of their joint resources. The partners are willing and able to adapt and innovate in the face of an uncertain and changing market.

Underpinning all elements of the spiral of success is communication – its quality, its timeliness and above all its openness. The partners recognise the cost of communication but realise that it’s an essential investment that invariably characterises a successful alliance.

The experience of Gibbs and Humphries is that many partnerships show characteristics of the spiral of failure, and sometimes accept it as a natural condition, arguing that the projected success spiral gains from partnerships are utopian and unachievable. In contrast their work has brought them into contact with others who seem to have the knack of working successfully in pairs, chains and consortia where efficiency, harmony and adaptability bring them tangible benefits. In reality most partnerships perform within a spectrum between these two extremes.

The extensive research undertaken by Gibbs and Humphries involving hundreds of substantial relationships in the private and public sectors across a wide range of industries, functions and cultures, has enabled them to identify the drivers, operational elements and behaviours that influence partnership outcomes. From an extremely large set of data, three “super factors” emerged as the salient drivers of partnership success.

Collaborative innovation

The conditions that describe the effectiveness of the relationship and enable the partnership to be innovative and to respond to opportunities. In essence the “spark” in the relationship. Comprised of: Adaption, Innovation, Communication and Cooperation.

Partnership quality

The overriding quality of the relationship exchange including synchronising joint objectives and the willingness to invest in joint assets such as people, know-how, training, IT and infrastructure which directly influence the quality and longevity of the relationship. Comprised of: Commitment and Trust

Value Creation

The efficiency of the partnership to create and capture the potential value that the partnership offers. Often involves a focus on the end customer and the sharing of the benefits of cost reductions and new business opportunities. Comprised of: Conflict Management, Synergy, Value Creation and Process Efficiency

Behind each of these “Super Factors” are a raft of questions that probe matters such as the partners willingness to change and innovate, whether they have joint goals and participate in joint planning, the reliability of the other party, the usefulness of communications, dispute resolution procedures, attitudes to each other and partnering and operations management.

When viewing relationships using these “super factors” matched to perceptions of success or failure, some clear patterns emerged. The vast majority of partnerships fell into one of eight partnership types. Most importantly, each type had a clear, individual character that led to an appreciation of the performance and management challenges that faced the partners. Each of the G & H Partnering Types takes on a personality and the chosen name reflects their main tendencies.

- Evangelists - appear as a marriage made in heaven and are usually good collaborators but may be prone to rest on their laurels.

- Stable Pragmatists - tend to be in a tough business but recognise that they are in the same boat and soldier-on doggedly, sometimes for many years.

- Rebellious Teenagers - almost your worst nightmare. A great partnership but challenging, annoying and very heated discussions.

- Evolving Pessimists - continually focus on what is not working rather than what is working well. They have good intentions but effective service-delivery is some way away.

- Captive Sharks - partnership hostages who work together because they have to. Usually proactively aggressive.

- Cherry Pickers - are just in it for the money and the short term, despite appearing at times to be committed.

- No Can Dos - in this relationship the businesses are simply pulling in opposite directions with no common ground. A history of bad behaviours and outcomes has ‘poisoned’ the atmosphere.

- Deserters - this stage typically precedes dissolution of the partnership or litigation.

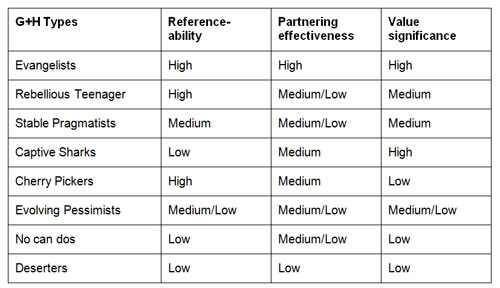

So how does one determine which G & H Partnership Type fits your strategic alliance? Although each one is defined by an extensive set of metrics, it is possible to get an approximate answer by considering a particular partnership in the light of the following three factors:

- Reference-ability

Our partner would provide us with a positive and flattering reference to a key customer or buyer.

- Effectiveness

In the last six months we have increased the level of satisfaction of our customers as a direct consequence of this partnership.

- Value

We have seen a real cost advantage/margin gain as a result of working with this partner OR we represent a significant share of this partner’s business.

ext plot your answer using a subjective High, Medium, Medium/Low or Low assessment into the following matrix:

Having ‘typed’ your relationship, what next?

Of course this will depend on which one you have identified. However, in general terms it is vital to share your findings with your partner – even better if you have carried out the exploration exercise together. You must then review your strategic objectives and ensure that you have a common understanding of how the alliance fits in.

This may require some realignments both jointly and individually. Next follows a tactical review. Carefully identify the sources of friction that undermine the effectiveness of the partnership - negative spiral behaviours. Often fixing minor operational issues will go a long way to restoring confidence.

Put in-place projects to address more fundamental problems; the overall aim is to improve effectiveness by cutting costs and inefficiencies. The alliance is doubtless missing opportunities to capitalise on its strengths – resulting from the positive spiral behaviours. Key to achieving these benefits is establishing good relationship management practices such as joint regular performance monitoring, problem-solving and planning activities. Providing a focus for the joint enterprise will ensure that continuous improvement replaces fire-fighting and stagnation.

In their book, “Strategic Alliances and Marketing Partnerships: Gaining Competitive Advantage through Collaboration and Partnering” (Kogan Page, London), Gibbs & Humphries take the reader step by step through the process of evaluating their important business relationships and locating them within the G & H Partnership Types. This takes place by completing simple worksheets at the end of each chapter so that by the time you get to the end you will not only know what Partnership Types you have to deal with but you will also have been given the detailed perspective needed to manage more successfully and achieve your competitive objectives.

Isobel Briggs Myers said: ‘Whatever the circumstances of your life, the understanding of type can make your perceptions clearer, your judgements sounder and your life closer to your heart’s desire’.

Gibbs and Humphries paraphrase this: ‘Whatever the circumstances of your business partnership, the understanding of type can make your assessments clearer, your management sounder and your actions better aligned to your objectives’.

Go back to Strategic Planning resources

Go back to main Resource Centre index

Andrew is currently CEO of SCCI Ltd which specialises in measuring commercial relationship performance. He completed a 34 year career in the Royal Air Force culminating as Head of UK Defence Aviation Logistics. Richard is a recognised expert in marketing channels and has held senior positions with Xerox and Novell Inc.